March Labor Report Comes in Ho-Hum

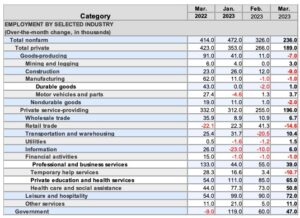

The March Labor Report ended up being “more of the same.” Job openings came in at 236K, and analysts were looking for 238K. The unemployment rate was 3.5%, and even the more aggressive U-6 rate was just a hint lower, falling from 6.8% to 6.7%. That doesn’t change the narrative much, but it also doesn’t give the Federal Reserve any indication that labor and unemployment is surging – which also gives the Central Bank the opportunity to continue to push rates higher at a slower rate. Average hourly wages were growing at 4.2% annually. This was the lowest level of wage growth since the economy was digging out of the lockdown period, but it is still above the long-term 2%-2.5% annual rate. Perhaps the challenge here is that average wages are still running a bit cooler than broader inflation (the two are obviously linked together since wages push average inflation higher – the wage-price spiral). Average inflation rates are still running at 4.6%, while wages are running 4.2%, which keeps the lower end of lower-income households still facing a drop in real earnings. The total number of jobs being created is certainly down month-over-month and year-over-year. Hiring is slowing. Total private industry hiring was 189K, down from 266K last month and down from 423K a year ago. So again, the private sector is slowing. Government hiring is also weaker, but still created 47K jobs in the month after adding about 119K in January and 60K in February. It is interesting to look at the industries laying off workers this month. Construction, non-durable manufacturing, retail, and temp help are seeing cuts. The drop in construction is a bit concerning, but this is a sector that could rebound in the coming months. The participation rate increased slightly which was a positive trend, and it was mostly men moving back into the workforce. Not that this change was significant (from 62.5 to 62.6), and it was still below pre-pandemic levels, but directionally it was a better trend. Again, this report didn’t change much of the narrative in the market, and it will push everyone to rely on other economic metrics to draw conclusions on the direction of the broader economy. The pessimists will see the deceleration and know that layoffs are trailing indicators, that wages aren’t coming down too quickly, and that there is enough in here to push the Fed to misread it and hike rates. Optimists are going to see that the economy still created 234K jobs in the face of a mini banking crisis, and companies seemingly had the wherewithal to keep wages growing at a healthy clip. Even the challenged high-tech sector was still finding pockets of hiring, enough so to keep job creation positive this month.

The March Labor Report ended up being “more of the same.” Job openings came in at 236K, and analysts were looking for 238K. The unemployment rate was 3.5%, and even the more aggressive U-6 rate was just a hint lower, falling from 6.8% to 6.7%. That doesn’t change the narrative much, but it also doesn’t give the Federal Reserve any indication that labor and unemployment is surging – which also gives the Central Bank the opportunity to continue to push rates higher at a slower rate. Average hourly wages were growing at 4.2% annually. This was the lowest level of wage growth since the economy was digging out of the lockdown period, but it is still above the long-term 2%-2.5% annual rate. Perhaps the challenge here is that average wages are still running a bit cooler than broader inflation (the two are obviously linked together since wages push average inflation higher – the wage-price spiral). Average inflation rates are still running at 4.6%, while wages are running 4.2%, which keeps the lower end of lower-income households still facing a drop in real earnings. The total number of jobs being created is certainly down month-over-month and year-over-year. Hiring is slowing. Total private industry hiring was 189K, down from 266K last month and down from 423K a year ago. So again, the private sector is slowing. Government hiring is also weaker, but still created 47K jobs in the month after adding about 119K in January and 60K in February. It is interesting to look at the industries laying off workers this month. Construction, non-durable manufacturing, retail, and temp help are seeing cuts. The drop in construction is a bit concerning, but this is a sector that could rebound in the coming months. The participation rate increased slightly which was a positive trend, and it was mostly men moving back into the workforce. Not that this change was significant (from 62.5 to 62.6), and it was still below pre-pandemic levels, but directionally it was a better trend. Again, this report didn’t change much of the narrative in the market, and it will push everyone to rely on other economic metrics to draw conclusions on the direction of the broader economy. The pessimists will see the deceleration and know that layoffs are trailing indicators, that wages aren’t coming down too quickly, and that there is enough in here to push the Fed to misread it and hike rates. Optimists are going to see that the economy still created 234K jobs in the face of a mini banking crisis, and companies seemingly had the wherewithal to keep wages growing at a healthy clip. Even the challenged high-tech sector was still finding pockets of hiring, enough so to keep job creation positive this month.

What is to Blame for Slow Global Growth?

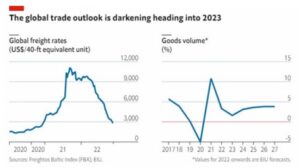

According to the IMF, the two most important inhibitions have been economic fragmentation and geopolitics, and these are closely related. The average pace of global growth has been 3.8% over the last twenty plus years, but the prediction now is for growth at 3.0%, the slowest pace since 1990. Obviously, there will be differences in growth rates between nations. The most worrisome aspect of the report involves the factors that have been slowing this pace as these are issues that will be difficult to address. This is not an issue rooted primarily in economics. This is not an absence of demand, or even of supply. In past years, the slowing pace could be attributed to commodity shortages, production shortfalls, demand erosion, and even weather events. This time, it is political strife that has deeply affected relations between the largest economies and complicated the development process in many nations. These challenges could be addressed by changing the political atmosphere, but that has proven to be nearly impossible given the orientation of those in power.

The first issue is fragmentation, or the shift away from the process of globalization. The globalization trend started in earnest in the 1980s and 1990s as the idea of a true global market evolved. It was a boon to consumers, but it came at the expense of workers in most of the developed world. It became possible for companies to produce in low-production cost environments efficiently. The keys were communication and transportation. There had always been an ability to make things anywhere, but getting these products to market was expensive and challenging. Globalization brought products from all over the world to the consumer and contributed heavily to almost thirty years of low inflation. There has always been opposition to this development from those whose jobs vanished and whose businesses were unable to compete, but the consumer won. Until recently. There had already been mounting pressure from political leaders seeking to protect domestic jobs and businesses, but the pandemic accelerated the change as the transportation and production systems started to break down. In the last several years, there has been the emergence of fierce nationalism and protectionism. There are now few political leaders or parties that favor trade. The US is a prime example. Even ten years ago there was substantial support for global business and trade within both major political parties. The GOP supported business, and the Democrats favored lower prices for consumers. Today, the GOP has become intensely nationalistic and populist, anti-trade and isolationist. The Democrats have become isolationist as well with more interest in jobs than consumer demands. Each day brings more trade restrictions. This is the same pattern seen in Europe and many other nations.

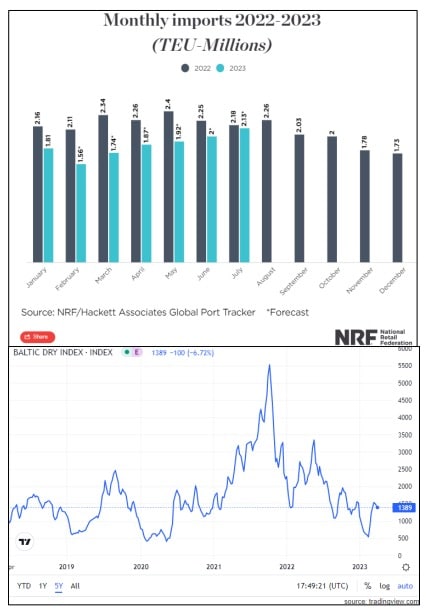

National Retail Federation Port Tracker Shows Incoming Volumes

If one needed proof of how slow conditions could be relative to last year, one doesn’t have to look any further than the NRF and Hackett Associates outlook for port volumes in 2023. Although, looking closely, there is some hope for a more traditional peak season.

Retailers have been trying to clear old inventory and are working on understanding what the demand environment looks like for the fourth quarter. But TEU volumes could begin to look slightly better than last year by the fourth quarter, if sell-through of products continues at current rates and inventories fall. The near-term volume being moved through the global maritime sector is weak, but that is expected to change by the end of the year.

There are also some concerns and uncertainty surrounding the West Coast port negotiations and the ability for China to ramp back up enough in its post zero-Covid policy era to keep pace with demand. That could push companies to try to build inventories a bit quicker than expected, fearing that they could tighten too much and actually run themselves short on inventory if there are delays in China restocking and resupplying.

Current manufacturing data would suggest that the global demand for products is not ramping up yet, but manufacturers are getting ready for what they believe is an uptick in demand by pre-staging raw materials. The index has softened just slightly in the past five days but continues to be higher than at any time since last summer. The second half of the year should continue to improve, and some supply chain challenges could surface as the globe enters the peak season. That would especially be the case if the economy continues to show consumer spending at current levels, job creation remains high, and unemployment rates remain low.