Where Were the Jobs Created?

The details cast in the jobs report give added clarity to the December report. Frankly, it is what one would expect through December. Most of the hiring in retail would have occurred in November, but anything that caters to the seasonal holidays got a nice boost in hiring (such as leisure and hospitality).

The breakdown by sector is listed below with the number of jobs created in December:

1. Leisure and hospitality 67,000

- Food 26,000

- Casinos 25,000

- Accommodation 10,000

2. Health Care 55,000

- Ambulatory 30,000

- Hospitals 16,000

- Nursing Facilities 9,000

3. Construction 28,000

4. Social Assistance 20,000

5. Mining 4,000

6. Retail 9,000

7. Manufacturing 8,000

- Durable 24,000

- Nondurable -16,000

8. Transportation and Warehousing 5,000

9. Government 3,000

10. Professional and Business -6,000 (temp services -35,000)

The BLS (for some reason) threw an odd statistic in the mix this month. They showed that employment in leisure and hospitality is still 932,000 lower than it was pre-pandemic.

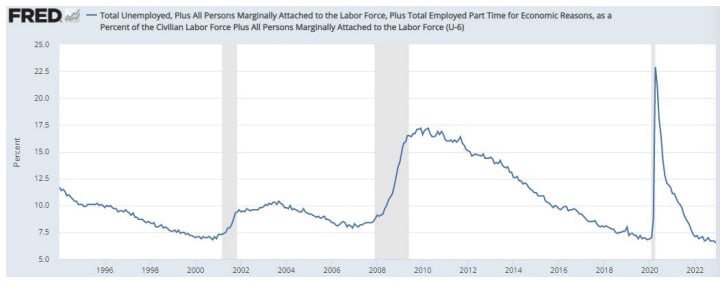

U6 Hits Lowest Level on Record

The standard unemployment is known as the U3 Rate. There is another measure called the U6 Rate. This unemployment rate includes the unemployed, those forced into part-time work, and those marginally attached to the labor market. It just hit an all-time low.

Sometimes the U6 is much higher than the U3, and it shows that household income is being squeezed more directly in some cycles. Right now, the opposite is occurring, and it helps explain why some consumer spending metrics are surprising.

The U6 is just 6.5%, giving the Fed some confidence that it has not overly tightened interest rates – yet. In most historical periods, hiking interest rates has a 3–6-month lag effect on the broader economy. The Fed Funds Effective rate started adjusting in March and had jumped nearly 2% by August. Right now, the economy is in that “window” in which the Fed doesn’t know how much the tightening will change the market, but as they try to turn this battleship, for the moment they aren’t seeing any portion of the front of the ship starting to turn despite yanking hard on the rudder.

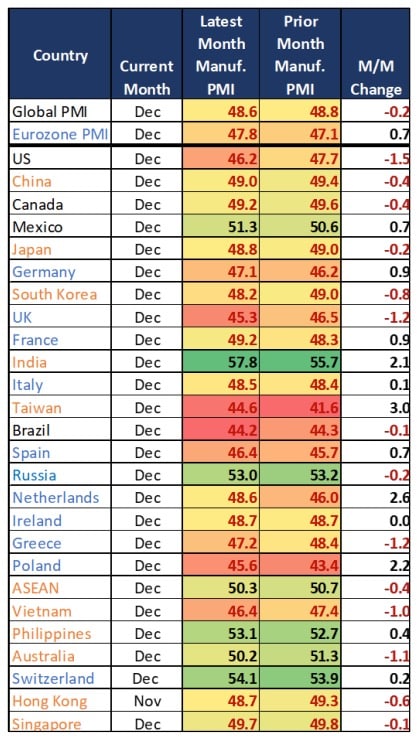

Manufacturing Flagging Recession

The global PMIs that were released recently continue to flash a global recession warning. Twenty-one countries have manufacturing sectors in contraction (under 50 PMI), just 7 were expanding in December.

The S&P Global PMI for the US came in at 46.2, firmly in contraction and down from 47.7 last month. Comments from S&P Global indicated that new orders hit lows not seen in nearly 16 years. That weighs on future manufacturing activity and indicates that much of the supply chain could slow in the first quarter.

Most of the reports from around the world showed that the biggest negative drag on global growth was coming from the US, China, and Europe. That is not surprising because Europe is being impacted by the war in Ukraine and China was impacted by Covid and its struggle to now get out from under its failed zero-Covid policy. But the US is also creating this reduction in new order demand from both domestic and import activity.

What could be more troubling in the December report is the notion that most manufacturers are clearing backlogs of work at this time. That is a good thing, but in this case, the majority of the output index is being driven by clearing backlogs. When these backlogs are cleared, there won’t be enough new order activity to keep their assembly lines in full production, and many are already forecasting the need to trim workers for a period of time.

The other issue to watch is the potential for significant profit pressures to emerge quickly. Many manufacturers were still reporting that input prices (materials, component parts) and operating costs (energy, labor, transportation) were still increasing. But factory output prices were retreating as companies were forced to discount products to try to move them. Although that deflationary trend is positive for the broader economy, the imbalance between input price inflation and factory gate price deflation is going to put pressure on manufacturing profits.

Or course, these are broad comments. Many industries will see steady levels of demand (automotive, aerospace, non-residential construction and supporting industries, etc.), and some sectors will not even know that a slowdown is at hand.

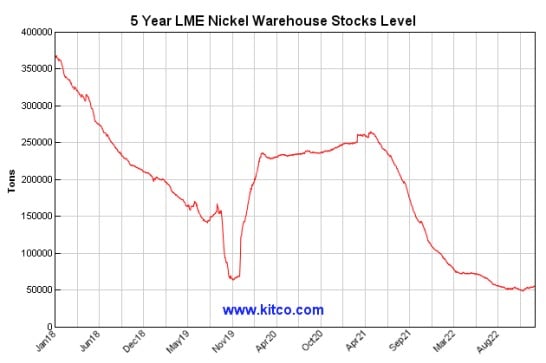

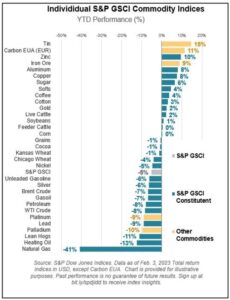

Confirmation of the Global Raw Material Supply Shortage

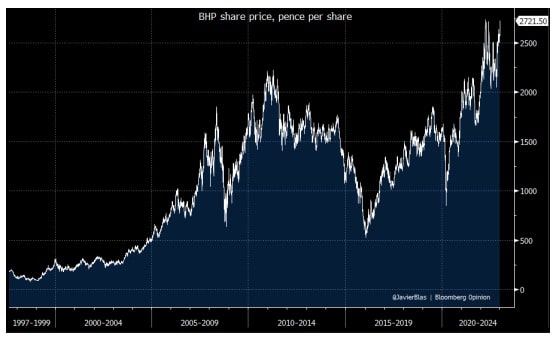

Javier Blas put a note out on BHP. The manufacturing sector may not be paying attention to the global problem with raw material supplies (especially metals like copper, nickel, iron ore, zinc, etc.) but investors are. Look at the chart for BHP (at right); it has just hit an all-time high.

The coming shortages of nickel could be a real problem when the global manufacturing sector is once again firing on all cylinders. Projecting forward three months, if China has weathered this wave of Covid and Europe has emerged from winter and warmer weather allows industrial production to restart, there could be some ramifications of this supply shortage at that time.

Again, investors seem to think that this could be the case. The nickel inventory chart shown (at right) from Kitco illustrates the lower inventory levels at this time (during a lower demand period for stainless steel).

This is one of the crosscurrents to watch in 2023 to see if some inflationary pressure starts to rear its head again in the summer and fall.